Rosamond Purcell's Art from Decay

Rosamond Purcell has a long history of providing inspiration to the Zymoglyphic Museum as a photographer of museum specimens, a scholar of curiosities, an exhibit curator, a writer, and an assemblage artist of decay. Her photographs of natural history museum specimens earned her a place in the museum's Photographers of the Marvelous online photography exhibit, and her use of natural light in these pictures has been an inspiration to our own curatorial department's attempts to document our museum's collections. One of her collaborations with Stephen Jay Gould, Finders, Keepers: Eight Collectors

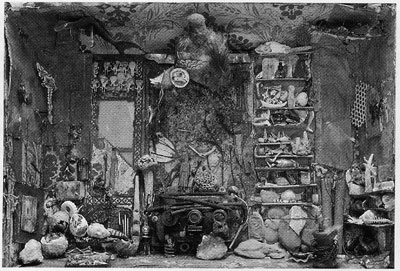

In 2003, Purcell curated a traveling exhibit called Two Rooms. One room was a reconstruction of a small but historically important natural history museum created in the 17th century by Ole Worm. The other room featured a reconstruction of Purcell's own studio/museum, with walls of rusted metal sheets, a library of decayed, worm-eaten books, and arrangements of a variety of objects transformed by nature and weathering. Most of these objects came from a single source, a vast junkyard in Maine which she has been mining for aesthetic gold for two decades, and whose story is told in the book Owls Head

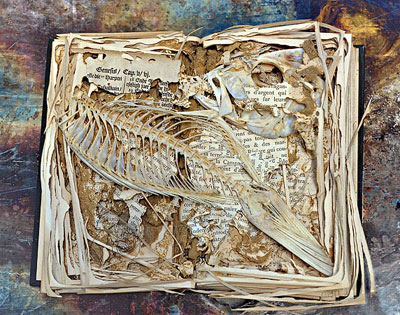

Her new book Bookworm: The Art of Rosamond Purcell

There seem to be still more Zymoglyphic inspirations which have yet be fully documented. Above are two photographs from "Two Rooms", the exhibition catalog. The top one is a "miniature museum" from 1994, similar in spirit to the Zymoglyphic shoebox art galleries and the bottom shows a number of objects on display in her studio, any of which would be at home in our museum.

Labels: Artists, Natural art, Photography

While some may question whether

While some may question whether  As I noted

As I noted  A lesser-known type of work that he does are "snowball paintings", which are created by putting a snowball stained with a natural dye on paper and letting it melt. The result is an amazingly detailed pattern created by the way the dye is deposited as the snow melts and the water evaporates. A detail from one is shown here, with an enlargement

A lesser-known type of work that he does are "snowball paintings", which are created by putting a snowball stained with a natural dye on paper and letting it melt. The result is an amazingly detailed pattern created by the way the dye is deposited as the snow melts and the water evaporates. A detail from one is shown here, with an enlargement